The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

02 August 2016 | By

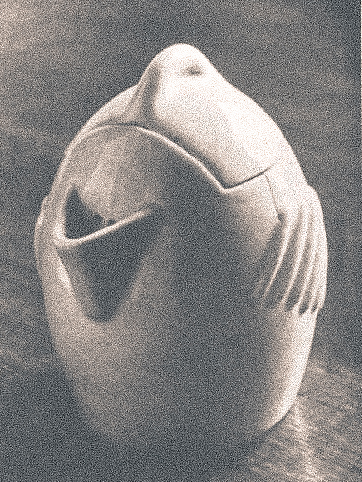

Tatlin modelling his utilitarian coat, the energy efficient oven is visible on the right, 1919

Of the plethora of artists’ manifestos published in the Soviet era, perhaps none has a more absurd title than Vladimir Tatlin’s 1930 work ‘The Problem of the Relationship Between Man and Object: Let Us Declare War on Chests of Drawers and Sideboards’. The treatise proselytises the new Soviet domestic aesthetic as a counterpoint to the bourgeois excesses of contemporary Western consumer products. Tatlin’s thesis was that by exploiting the inherent qualities innate to a particular material, one could create objects that aptly fulfilled their function without the need for any ornamental decadence. In this way he designed a child’s drinking vessel, a utilitarian worker’s jacket, an energy efficient oven, and, most intriguingly of all, a chair that was meant to replicate the experience of drifting upon a cloud. A friend recalled:

“He dreams of designing a chair for people engaged in intellectual pursuits that would make a person feel as if he were sitting ‘on a cloud’. So that the body would relax by equally distributing its weight ‘onto all points’. And a kind of electric cap would hang over one’s head and by means of special ‘magnetic rays’ would absorb all tiredness from the person, leaving him refreshed, after which he would go back to work!’’

Prototype bentwood chair, an experiment towards the attempted cloud chair, 1927

The chair of course proved to be chimerical and all attempted designs were apparently extraordinarily uncomfortable to sit in. In this regard Tatlin’s cloud chair is often juxtaposed with his preposterously colossal ‘Monument to the IIIrd International’, and his doomed ornithopter ‘Letatlin’, as the slightly deranged, fantastical imaginings of the eccentric avant-garde artist. However this is to ignore the panoramic influence of the notion of ‘novyie byt’ (‘new daily life’) that pervaded the contemporary Soviet imagination. ‘Novyie byt’ symbolised the utopian embrace of communal living as an antidote to the pernicious practice of private dwelling. The new forms of quotidian life were a means by which to restructure daily behaviour and ultimately even human nature itself. Tatlin clearly had a deep conviction in such ideas. His manifesto’s stated goal was to create ‘an object which is original and radically different from objects in the West or in America. This last fact is very important in-as-much as our everyday life is being built on completely new principles.’

A child's drinking vessel, 1930

Tatlin’s cloud chair, though fantastical in its ideals, was nevertheless functional in its aims of replenishing the energy of workers, presumably to power them on to another Stakhanovite shift. The work also suggests the influence of cosmism upon Tatlin’s oeuvre. The philosopher Nikolai Fedorov, in his influential work of 1913 ‘The Philosophy pf the Common Task’, had theorised on humanity’s potential to harness the electricity within the Earth’s atmosphere and ultimately to thermostatically control the forces of nature. Furthermore the Futurist poet Velimir Khlebnikov (with whom Tatlin collaborated on occasion) in his 1918 poem ‘Skybooks’ envisaged projecting the latest news directly onto the clouds as a means by which to educate the proletarian masses. There has even been some suggestion that Tatlin’s tower was to be equipped with projectors for this very purpose. Long before Apple had devised the supposedly innovative idea of storing information in a metaphorical cloud, the Russian Avant-Garde were exploring the idea of doing so quite literally.