The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

When I say ‘abroad’, I don’t mean away from Russia, but away from Paris.

Sergei Diaghilev’s troupe of Russian dancers never actually performed in Russia. Paris is usually regarded as their hub: this is where the company first formed in 1909 and where the majority of its premieres were held. Paris was the source for much of the Ballets Russes aesthetic, and many of their contributors were either French or foreigners based in Paris.

But what if we were to plot all of the Ballets Russes’s movements on a map, from their founding in 1909 to their disbandment in 1929? This would not have been easy to do in any accurate way until quite recently. It was Jane Pritchard, Curator of Dance at the V&A, who painstakingly put together the first systematic itinerary for 2010’s wonderful exhibition, Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes.

Ballets Russes performance venues in Europe, 1909–1929

When we look at the map, it reveals just how far and how frequently the company travelled – a fact that is often overlooked by the general emphasis on first nights and on Paris. The scale of their travels becomes all the more impressive when we remember that this was a time far less globalised than the present. It also shows just how hard dancers and staff must have worked.

On the road in rural Spain

Interestingly, Pritchard calculates that only 9% of Ballets Russes performances took place in Paris (and only about 11% in France as a whole) whereas about 47% took place in Great Britain, the majority of which were in London. Performances ‘abroad’ from Paris were also richer: the focus in Paris was on novelty, but on longer tours the company offered a more varied repertoire.

If we look at just a few examples of other cities in which the Ballets Russes performed, Monte Carlo occupied a special place in Diaghilev’s heart. It was there in 1911 that he founded the company as a permanent troupe, and in the 1920s it became a sort of creative workshop for the group. It was a space for rehearsal in the lead up to the important Paris and London seasons, and a number of ballets were created there: Le Spectre de la Rose, Narcisse, Daphnis et Chloe, Les Noces, La Chatte, Le Bal.

Rehearsal for Les Noces on the roof of the Theatre de Monte Carlo, 1923

Travelling was key to the Ballets Russes aesthetic. Someone like Mikhail Fokine had already travelled a great deal before the company was even formed: he went all through Russia, to Italy, Vienna and Budapest, collecting postcards and recording details of local customs, folklore and dance. You can see the same fascination with non-Russian folk ballets in Goncharova’s designs. The company had spent much time in Spain, yet it was in Rome that Goncharova created designs for Espana. There she socialised with Diaghilev, Jean Cocteau, Satie, Picasso, important Italian composers and, of course, the Italian Futurists. Melting pots of artistic creativity formed wherever Diaghilev went, and many a ballet came out of this.

Ballets Russes performance venues in North America, 1909–1929

A lot of the ballets from this time on, during WWI and afterwards, featured music from foreign composers – the music of Gregorio Martinez Sierra for Le Tricorne, the work of Ravel for Goncharova’s Espana. I believe this movement away from the earlier Russian/Parisian core was made by choice, but also by necessity. Artists and dancers kept their eyes open throughout the company’s travels and were genuinely inspired by the immense variety of what they saw. The outbreak of the First World War, which pushed the company away from Western Europe to a certain extent, and forced Diaghilev to base himself in Rome and to launch a North American tour, also made a big difference. Four years seems little when thought of in retrospect; but when you consider how long four years actually feels, you can understand how cut-off they must have felt. This is especially the case after the Revolution, which separated the dancers from their homeland.

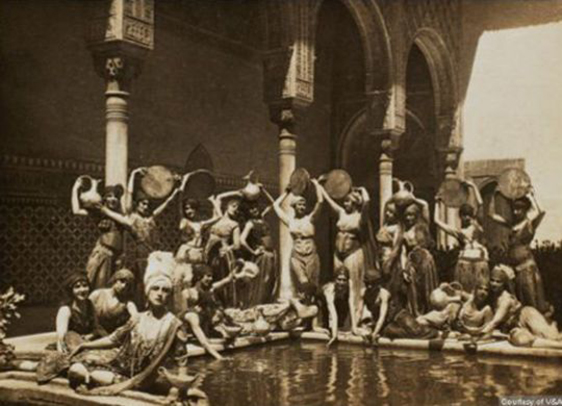

The Ballets Russes en route to South America, July 1917

I believe you can look at ballet much as you would a painting. A painting’s meaning changes depending on time, location and who exactly is viewing it. The same idea of reciprocity between audience and performers exists in ballet – and here I wonder in particular about the importance of location.

Ballets Russes performance venues in South America, 1909–1929

We need to think more about what it means to be a travelling company and how this affects artistic inspiration. This ties in with an important theme in twentieth-century Russian art history – that of the émigré artist. What is the difference between moving once and moving constantly? Do you become more nationalistic, or do you absorb the different cultures that you encounter?