The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

17 May 2016 | By

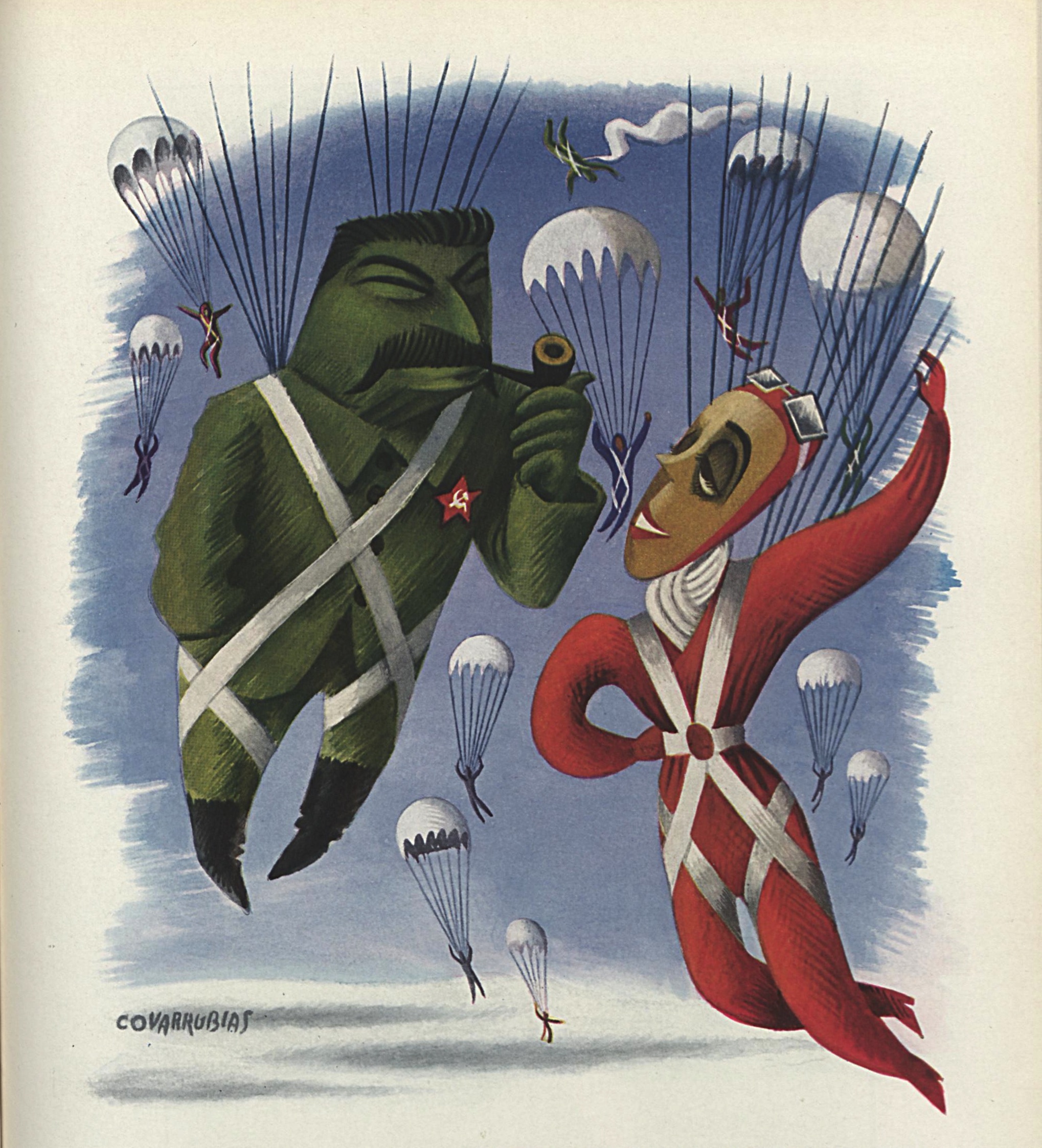

Being a press genre of a generally unpolitical nature, fashion magazines very rarely instrumentalise political symbolism for their purposes, with the exception of fashion journalism in the era of the Soviet Union, when it was internationally a common practice to mock the "Comrades" for their lack of attention towards fashion and female elegance. When Stalinism was flourishing in the 1930s, American Vogue published what must be the wittiest illustration the periodical has ever produced, depicting an imagined conversation between the dictator of Soviet Russia, Stalin, and the dictator of Paris Fashion, Elsa Schiaparelli. Published in the mid-June 1936 issue, the "Impossible Interview: Stalin versus Schiaparelli" illustrated by Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias shows the protagonists in a heated dispute over the Soviet woman's entitlement to fashion:

Stalin: What are you doing up here, Dressmaker?

Schiaparelli: I am getting a bird's-eye view of your women's fashions, Man of Steel.

Stalin: Can't you leave our women alone?

Schiaparelli: They don't want to be left alone. The want to look like the other women of the world.

Stalin: What! Like those hip-less, bust-less scare-crows of your dying civilizations?

Schiaparelli: Already they admire our mannequins and models. Sooner or later they'll come to our ideals.

Stalin: Not while Soviet ideology persists.

Schiaparelli: Look below you, Man of Steel. Look at the beauty parlours and permanent-wave machines springing up. The next step is fashion. In a few years, you won't see kerchiefs on heads any more.

Stalin: You underestimate the serious goals of Soviet women.

Schiaparelli: You underestimate their natural vanity.

Stalin: Perhaps I had better cut your parachute down!

Schiaparelli: A hundred other couturiers would replace me.

Stalin: In that case, cut my ropes!

.jpeg)

Other than serving a merely satirical intention, this Vogue page pinpoints a development in Soviet dress behaviour in the years following the systematic undermining of fashion and sartorial luxury in the 1920s and hints at Elsa Schiaparelli's attempt to dress the Russian woman in 1935. Being criticized by fashion journalists for being poorly dressed, female workers of the USSR required a helping hand, which the Soviet government planned to provide in Elsa Schiaparelli. In winter of 1935 she was invited to visit Moscow and design suitable workwear for the female population of Russia, coinciding with the opening of the Dom Modelei (House of Prototypes). Following this invitation, Schiaparelli set out for Moscow in November of 1935, accompanied by British photographer Cecil Beaton, to present her capsule collection, attend social functions and even visit the Kremlin’s treasury. For dressing the Soviet woman, she had envisioned a practical black wool jersey dress with a little turn-over collar of white piqué and a box calf belt, combined with a simple three-quarter coat of red felt with large black buttons, both with a little knitted hat reminiscent of a military pilotka cap. At the first Soviet Trade Fair in Moscow (the first capitalistic exhibition of its kind in the USSR), Schiaparelli’s inventions were presented to their target audience, failing to cause the expected enthusiasm about a leading Paris couturière designing for Russia's women. Schiaparelli’s coat and dress ensemble never went into production for authorities saw a danger in the big pockets on both garments and predicted that they would most likely attract pickpockets on the Metro. While the Paris designs eventually missed their intended effect on Russian dressing habits, the Russian capital seemed to have made a visible impact on Schiaparelli. Returning to Paris, she introduced parachute-skirt dresses in her spring 1936 collection, inspired by the parachute jumpers she saw during her trip to Russia. American Vogue concluded: "Practically every single time that Schiaparelli buys a railway ticket, there are fruitful consequences for this world of ours".