The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

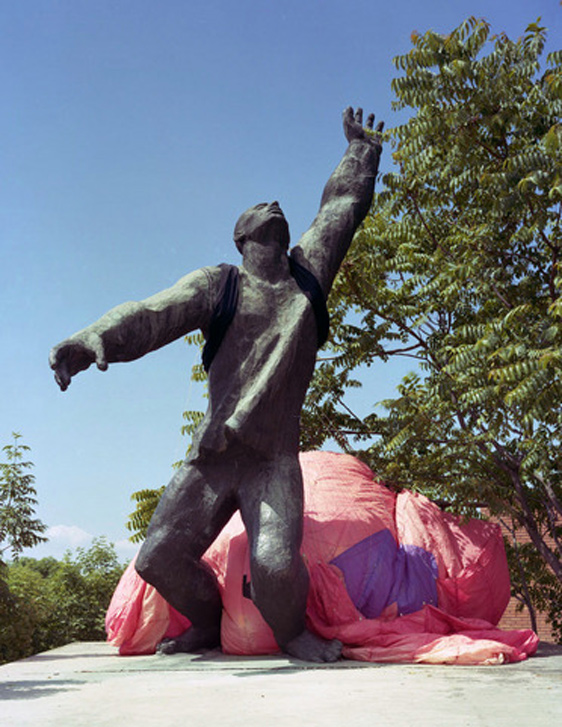

Imagine if you will a typical Soviet-era statue (take your pick from heroic worker, soldier or leader). Among the desired emotional reactions are admiration, faith in the regime, even fear perhaps. I certainly remember feeling some of these when confronted with such statues; that is, before coming across artist Liane Lang’s work, ‘Monumental Misconceptions’.

Liane Lang, In the Way, 2009

In 2009, London-based Lang took up an artist's residency in Budapest’s Memento Sculpture Park (a resting place for discarded monumental sculptural works that were ripped down after communism fell in Hungary). While there she integrated life-size cast figures into the original bronze sculptures scattered about the park, forming what the artist refers to as ‘interventions’. These altered statues were were then photographed to produce wonderfully confusing and contemplative images. The mischievous positioning of the inserted figures throws into juxtaposition the life-size and the monumental and the (convincingly) animate and inanimate, forcing you to re-examine these historical relics in a new context. Some interventions add humour; others are subtler, adding tenderness and a touch of humanity. The female figure cradled across a handshake in in ‘Support Group’ below, entirely changes how we see what is otherwise a stern and masculine gesture.

As all 42 sculptures in the park are male and all of Lang’s figures female, I wondered if she had consciously decided to address feminist issues. When I put the question to her, she said that as a was female artist this was perhaps inescapable. She explained that it was a deliberate decision to introduce women who were very non-heroic and vulnerable, thereby heightening the contrast between intervention and statue.

Liane Lang, Support Group, 2009

During the interview I had the chance to further probe Lang’s motivations behind ‘Monumental Misconceptions’. Far from setting out to criticise communism, the artist was interested in raising the question of how context and history can influence our perception. Lang strongly believes that all art is made under the constraints dictated by the time it is made in; the constraints peculiar to Soviet-era sculpture are obvious, but she argues that there is no such thing as absolute artistic freedom even in today’s democracies. So, what then happens to an artwork's meaning once its original context has receded to the distant path? Should our treatment of it change? Lang’s work aims to set the viewer’s mind ticking along these lines, while bestowing a new context on the original Soviet sculptures.

An echo of these ideas can be found in a quote from Budapest’s Memento Sculpture Park’s architect and founder, Akos Eleod: ‘This park is about dictatorship, but as soon as it has been talked about, described and built, it is already about democracy. After all, only democracy can provide the opportunity for us to think freely about dictatorship, or about democracy, come to that, or about anything.’

Liane Lang, The Parachutist, 2009

All images are courtesy of the artist. A book based around Monumental Misconceptions titled ‘Amnesiac Patina’ will be available from 18th July 2014, and works from the series are currently on show at the Musee Beaux Arts Calais.

The exhibition runs until August 2014.Rachel Hajek