The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin (Verevkin in Russian) was born in Tula near Moscow but spent much of her life in Western Europe, first in Munich as the partner of Alexei Jawlensky and then in Switzerland. The Werefkin Foundation in Ascona, where Werefkin lived later in life, holds about 70 of her paintings and 160 of her sketchbooks.

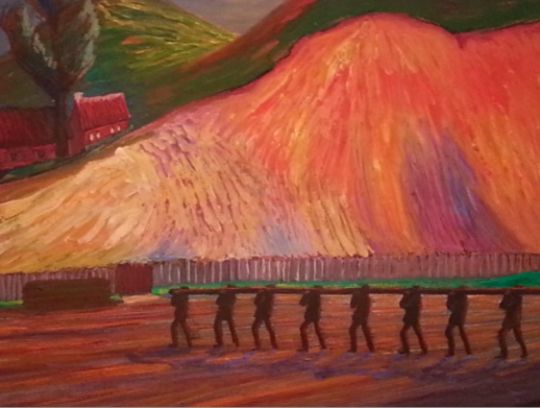

While her expressionist use of colour may derive from the Western influences of Van Gogh and Gauguin, her themes are northern, reflecting a harsher geographical and psychological reality, closer to that of Edvard Munch, and in content, though not in style, the social concerns of the Russian peredvizhniki. Her teacher Ilya Repin’s Barge Haulers on the Volga (1870-73) has some of the desperation and pathos of hard labour that we find also in Werefkin’s The Mine. Werefkin’s family estates were in Lithuania, from where she wrote to Jawlensy, then in Munich, in 1910: ‘All that is here is suffering and this horror of beauty and this horrible life and this overbearing literature, and the complete superfluousness of art.’

Yet Werefkin made art from the very material that so appalled her, deploying the expressive colour combinations used by Jawlensky and other members of Munich’s Blaue Reiter group, of which she was an early member. Against these infernal colours stumble the silhouettes of her burdened, faceless workers – ‘Some black figures – and the heart is heavy’ she wrote to Jawlensky. In her mature pictures black is the counterpoint – in figures, trees, mountains – to the flaming reds and lurid violets of her landscapes. Displacement and personal alienation – the lot of the emigree artist – and the challenge for a woman artist in a largely male community, find their way into her highly individual visual world. Her women have presence and assert themselves in her pictures whereas her men, as in The Mine, are often reduced to ciphers showing some kinship with L. S. Lowry.

Nihilism and regret are nevertheless turned by her painterly alchemy into a solemn beauty, far removed from the realism of Repin, with roots instead in the symbolism of Baudelaire and Poe, and the dark visions of Mikhail Vrubel. An authentically Russian vision is to be found on the bright shores of Lake Maggiore.