The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

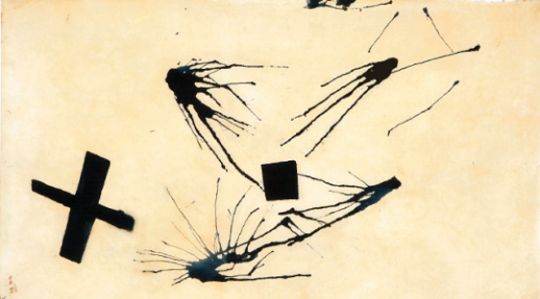

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

With this colourful exhibition, Palazzo Strozzi breaks new ground. Most people are aware of England and France’s empires, but do not know that the Russian empire—which started in 1552 with the conquest of the Khanate of Kazan, followed by the Khanate of Astrakhan (1556) and the Khanate of Crimea (1783)—stretched from the borders of Poland to the Sea of Japan. One can fit the entire continental United States of America into Siberia and there would still be some Siberia left over. The vast spaces of Siberia were—and still are—inhabited by tribes who believe that everything around them was animate, possessed of personality and living force. Their mediators with this world were shamans, about whom we learn much in the exhibition and its catalogue.

But first a caveat: this prodigious exhibition is misrepresented, in my opinion, by the inclusion of the much-overused and, in this case, misused term avant-garde in its title. In speaking with all three of the show’s curators, they made it clear that they preferred their original title, ‘Fire and Ice,’ which would have referred to the scorched deserts of the eastern Russian empire, known as Turkestan, and to its frozen Arctic regions. Most of the artists included in the show belonged neither to the early nor to the later Russian Avant-garde, a name assigned to radical, innovative artists and movements that started taking shape between 1907 and 1914, coming to the foreground in the revolutionary period, and the post-revolutionary decade, after which Socialist Realism took over.

The colourful and figurative, non–avant-garde contents of the exhibition are a good example of what happens when the abstract theories of three highly intellectual art historians meet the realities of the vast body of Russian art. Siberia and the East are part of every Russian artist’s DNA, since Russia was under the Mongol yoke for several centuries, thus the expression: ‘scratch a Russian and you will find a Tartar.’ The exhibition includes work by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes artists Boris Anisfeld, Léon Bakst, Alexandre Benois, Nicholas Roerich, Sergei Sudeikin and others, who designed wonderful oriental or Siberian costumes as well as settings for ballets that continue to be danced and admired a century later. None of these artists were considered members of the Russian Avant-garde.

The most significant pictures within the context of the show are those by Roerich: The Great Sacrifice, Exorcism of the Earth, Omen and Idols, which all illustrate some aspect of shamanism and spirit worship, as well as Konstantin Korovin’s Remains of a Samoed Encampment, showing votive ribbons on reindeer horns. Reindeer and their horns were considered sacred amongst the northern tribes, for they were the mount of shamans.

Il'ia Mashkov, whose portrait Lady in an Armchair (1913) is on the cover of the catalogue, belonged to the school of Russian Neo-primitivism, which encompassed work executed in a naïve style and frequently made reference to children’s drawings and toys, embroidery, hand-painted trays, shop signs, icons and Russian woodblock prints (lubki). Some members of the Russian Avant-garde, such as Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov, also sought inspiration in this Russian source material.

Several of the essays in the informative catalogue describe various aspects of Shamanism, which represented (and still represents) a worldview that assumes the unity of mankind with nature. With the advent of Buddhism in Russia in the seventeenth century, Shamanism and Buddhism coexisted and eventually became a hybrid religious system, particularly amongst the Buryats, Kalmyks and Tuvans. This is still the case in the Republics of Altai, Khakasia and Tuva today, where both Buddhism and Shamanism are thriving. Shamans like the one portrayed in Grigorii Choros-Gurkin’s splendid portrait, Baichak, the Shaman, still exist, and shamans’ drums and other objects used in shamanistic rituals are to be seen outside of museums in the Altai and Tuvan Republics and in Khakasia, as I saw earlier this year. The Strozzi Foundation is to be congratulated on having brought together so many fine works, several never exhibited before, as well as the ethnographical material almost totally unknown outside Russia except to a few archaeologists and ethnographers. This exhibition should be visited with wide-open eyes in order to absorb the unusual juxtaposition of 79 colourful paintings, watercolours and drawings, stone idols, 15 wooden sculptures and 36 Oriental artefacts and ethnographical objects. Furthermore, it is an exhibition to be recommended for family outings: children are bound to be intrigued by the anthropomorphized tree exhibits, votive animals and pictures of the Russo-Japanese maritime battles.

The article was originally published in The Florentine, issue №190/2013, 10 October, 2013.

The Russian Avant-garde: Siberia and the East Until January 19, 2014 Palazzo Strozzi Piazza Strozzi 1, Florence Hours: daily 9am to 8pm (Thursday extended hours to 11pm) www.palazzostrozzi.org.