The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

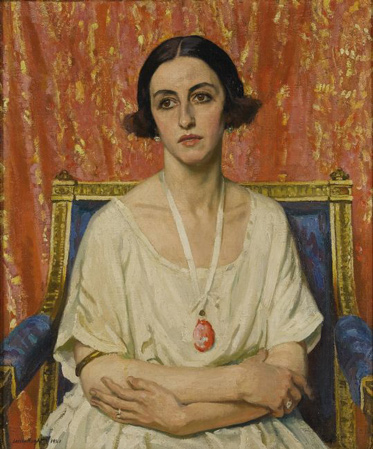

An exhibition of the portraits of Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970) travelled from the National Portrait Gallery to the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle, where I caught up with it in its final days.

Knight combined a fascination with the theatre, and a great facility in drawing scenes both on- and back-stage, with considerable later success as a society portrait painter and war artist. In 1936 she became the first woman to be elected to the Royal Academy, and her long life embraced radical changes in the European and World order. Her sensitive study of her near contemporary, the Russian ballerina Lubov Tchernicheva (1890-1976), made in London in 1921, and so much more persuasive than much of her later work, perhaps reflects the personal and visual delight she took in her association with the Ballets Russes.

Her second autobiography, The Magic of a Line (1965), speaks excitedly of her contacts with Sergei Diaghilev and his company in London, where Knight came to live after World War 1: ‘Diaghilev’s Ballet had made a sensational impact on the art of the theatre…’, she enthuses, ‘… he combined all the theatrical arts as had never been done before.’ For the second season she obtained a free seat in the house. ‘That was the season when, for three weeks, Pavlova starred with Nijinsky on alternate nights with Karsavina…all London went half mad with excitement.’ For the third season, in 1919, she obtained permission ‘to work wherever I liked in whichever theatre the Ballet was playing’, and we are indebted to her for a vivid and spontaneous visual and written record of these events. She conspired with Lydia Lopokova to use her dressing room as a studio and describes the clutter of that great dancer’s room with an artist’s eye: ‘The dressing table, crowded with pots of creams, powder puffs, trays of make-up, a comb, and pink ballet shoes with ribbons hanging down – all mirrored in the looking-glass behind – is ready for a still life study.’

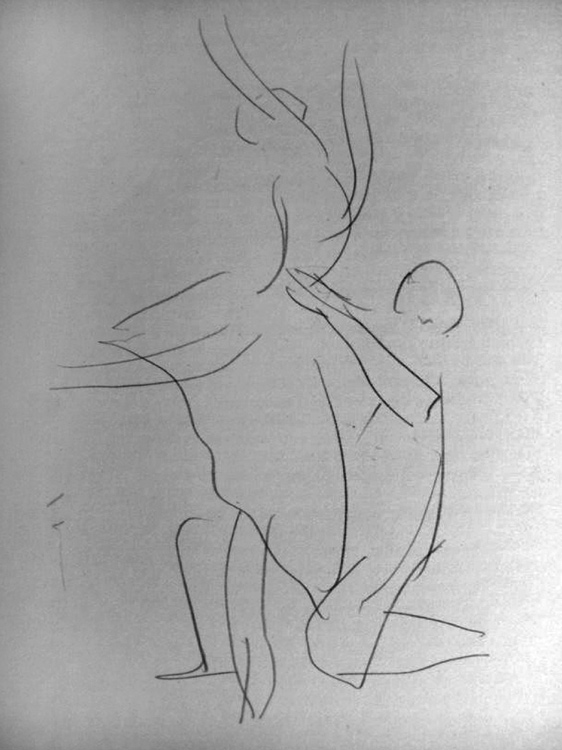

Knight was a determined balletomane. ‘During the 1920s and 30s, when the seasons spent by the Diaghilev Ballet in London were frequent, I could have been found back-stage every show, trying to draw all the wonderful subjects I saw.’ In her sketches she perfected a fleeting yet supple line in which movement and equipoise are conveyed with great economy.

Ballerina and Partner, 1928

A friend and confidante of Anna Pavlova, she nevertheless reserves her greatest praise for the work of Diaghilev. ‘In his presentations, any one of his performers, whether playing major or minor roles, was one instrumentalist among other instrumentalists, each belonging to a harmonic whole rather than an exponent of individual artistry.’ By contrast, ‘Pavlova was the sole virtuoso of her company’.

Tchernicheva studied at the Imperial Ballet school with Fokine and later with Enrico Cechetti – whom Knight also knew and sketched in London. Joining Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1911, she became a principal dancer with the company until his death in 1929. She danced Fokine roles and created new roles with Massine, Nijinska and Balanchine. She became Ballet Mistress to the Ballets Russes in 1926 and in 1932 joined the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. Settling finally in England she worked with Sadlers Wells, The Royal Ballet and London Festival Ballet.

Although the dancer and creator of many leading roles, Knight has chosen to paint Tchernicheva, in her studio in St John’s Wood, without any trappings of the theatre. This is a cool, elegant study of a woman of beauty and poise, with a hint of melancholy possibly prompted by the chaotic situation in her homeland at that time. The strong shoulders and arms form a graceful oval (enhanced by the much smaller oval of her pendant) suggesting at once athleticism and femininity, which, together with the curtain behind, and careful staging of the image, demonstrate Knight’s understanding that (as she later wrote of Pavlova) ‘…as well as a supreme artiste [she] was a woman.’

We sense that two professional women in the public eye, contemporaries confident in their artistic powers, were meeting here in a private space as equals.