The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Was Olga Rozanova cheated out of her place amongst the ‘greats’ of modern abstract art? She certainly thought so.

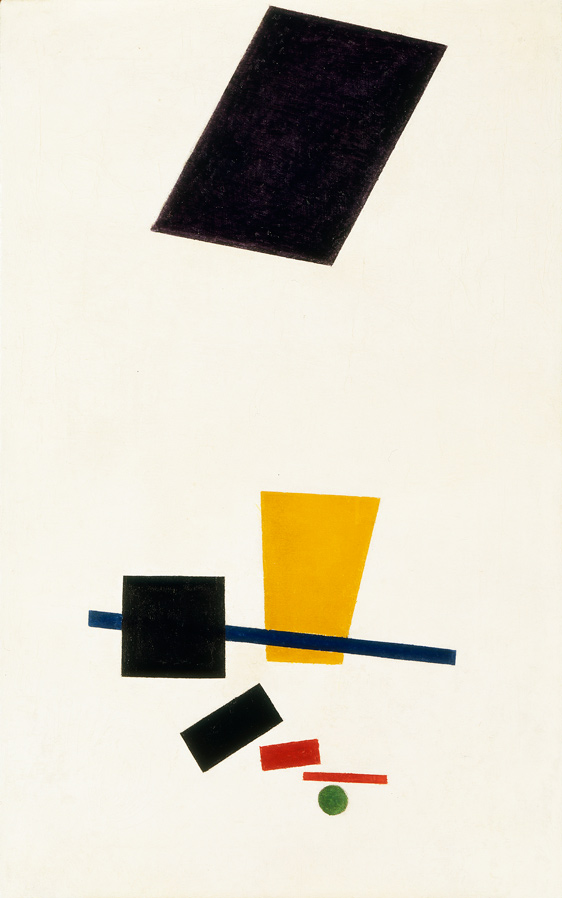

When she first saw Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematist paintings, combining abstract shapes in bold colours, she noticed a striking similarity with her own work. Angry and suspicious, in December 1915 she wrote to her partner, the poet Aleksei Kruchenykh:

“All of Suprematism consists entirely of my collages, combinations of surfaces, lines, discs (particularly discs) and totally without a realistic subject. In spite of all that, that swine doesn’t mention my name (…) Did you show Malevich my collages, and when exactly?”

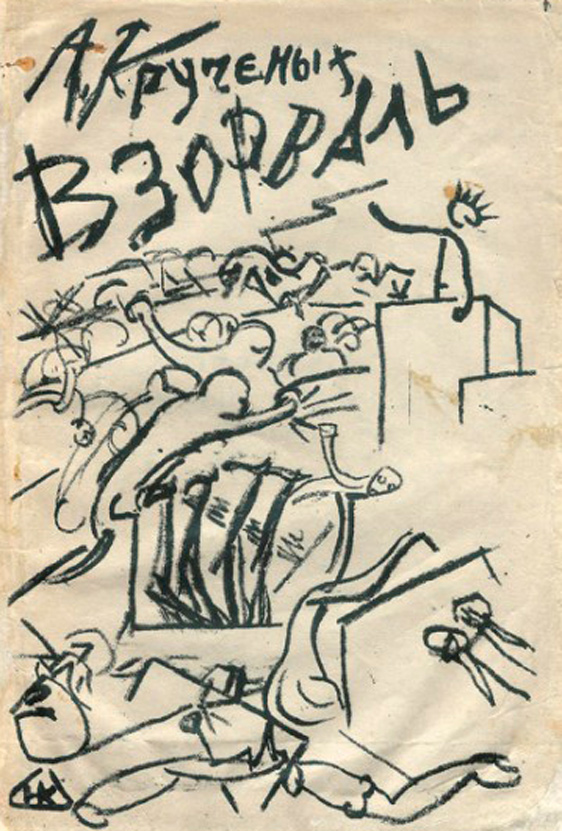

Kazimir Malevich, Prayer, illustration for Explodity by Aleksei Khruchenykh

There are several reasons why it’s difficult for us, 100 years later, to disentangle the order of artistic discoveries amongst Russian avant-garde artists. One is that Malevich had a habit of ‘back-dating’ his work: he often labelled his paintings with the date when the idea first occurred to him, not when he actually put paint to canvas, which was sometimes several years later. Rozanova, for her part, hardly ever dated her works at all.

Another complication is that many artists worked in collaboration with each other, so ideas were shared among the close artistic community long before they went on public display and acquired an official date. In many cases, at this remove, it’s simply impossible to put an accurate date on a work.

It seems that Rozanova arrived at abstract art via collage, rather than easel painting. She incorporated elements of collage into her paintings on canvas, but also developed her ideas in her designs for Futurist books. From 1913 onwards she collaborated with Kruchenykh to produce illustrated poetry books, which were radical both in their language and their aesthetics.

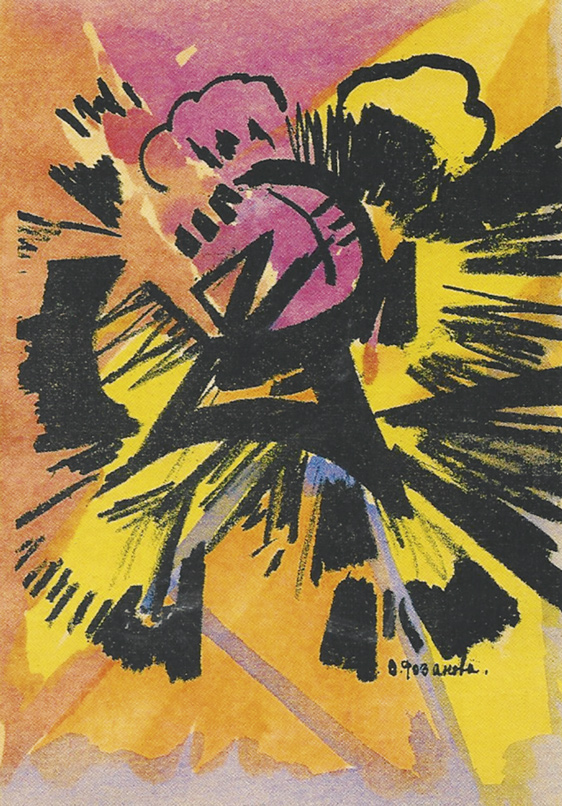

Olga Rozanova, Explosion, illustration for Explodity by Aleksei Khruchenykh

Kruchenykh was a pioneer of zaum – ‘transrational’ or ‘beyondsense’ poetry –which deconstructs the word, and suggests meaning through sound and intuition rather than literal definitions. It is abstract, both constructed from and essentially about words; obsessed with the word or the letter as an object rather than a means of conveying an idea. Similarly, many of the illustrations and collages that Rozanova produced for the books use colour and line not to signify something concrete, but to construct a whole new system of representation. In fact, at the time, abstract art was often known as ‘transrational’ art, underlining the connection with zaum poetry.

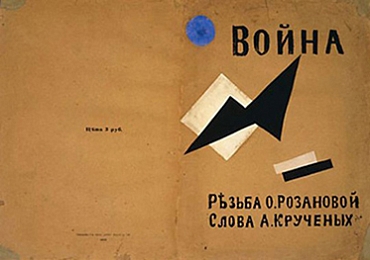

Olga Rozanova, cover for Explodity, 1913

The books were controversial, and the artists knew it. The front cover of Explodity (1913) shows an impassioned speaker on a dais hurling something (a bomb? A book of poetry?) into a chaotic crowd, as a lightening bolt splits the air. It seems to be saying: “this is what a revolutionary idea looks like”.

Kazimir Malevich, Painterly Realism of a Football Player, 1915

Rozanova’s collage for the front cover of War (early 1916) does bear an unmistakable similarity to Malevich’s Suprematist paintings. But does it ultimately matter who inspired whom, or whether they both arrived at the same idea independently? Perhaps it is just worth remembering that focussing on the 'big names' of art history tends to block our view of the smaller ones.