The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

28 July 2015 | By

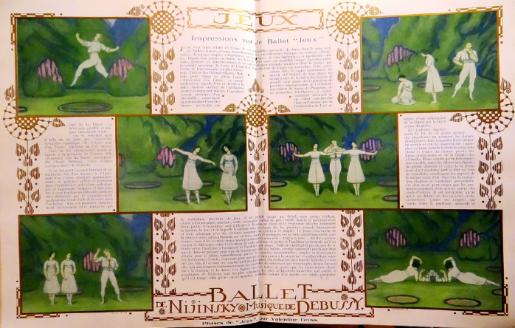

The ballet was not well received by the expectant Paris audience. Those who were not outraged by the suggestive ménage à troi scenario, were merely puzzled by the odd set up of three young people in a park at twilight, dressed for tennis but merely engaging in a playful flirtation rather than a game of sport.

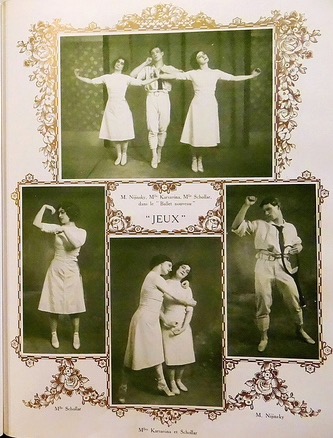

Studio photographs of dancers Nijinsky, Karsavina and Schollar

Overshadowed by the excitement surrounding L'après midi d'une Faune, Nijinsky's first choreographic achievement the previous season, and soon eclipsed by the scandal provoked by Le Sacre du printemps, premiered two weeks later, after only eight performances Jeux was dropped from Ballets Russes' repertoire and largely forgotten.

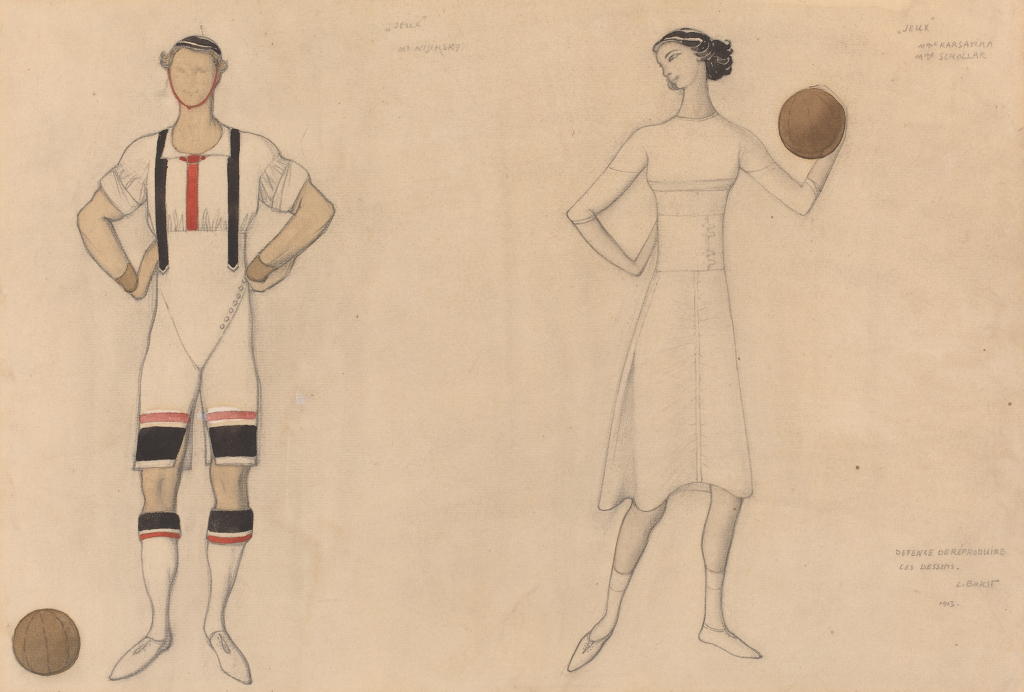

Although it is the least documented of Nijinsky's choreographed works, a number of illuminating materials survive. These include various studio photographs, six pastels by Valentine Gross, a selection of Bakst's costumes, (although not all were used in the performance), both Debussy's and Nijinsky's marked scores, along with a bar by bar description of the action, critical reviews and reminiscence from performers and their contemporaries. This has helped dance historians piece together the lost work and reassess its significance.

Preliminary costume designs by Leon Bakst

Originally considered of minor importance, Jeux in fact demonstrates innovation in every aspect of the 'poème dansé'. From the theme and scenario, to the aesthetic values, to the development of the relationship between movement and music, Jeux was an extraordinarily modern ballet. Unlike Nijinsky's more famous works, which aimed to reproduce artworks from Classical Greece or rituals from Russia's pagan past, Jeux was focused on uniting ideas and styles of contemporary art with dance. Although the origins of the ballet are claimed by three differing accounts, all agree on the desire to create a portrait of a modern man. Nijinsky and his collaborators attributed their inspiration to the Cubists and Futurists. Balletic movements were fragmented into short snap-shot like sections, giving the impression of a a series of photographic frames. These angular movements, branded by the audience as ugly were deemed too radical and far removed from traditional ballet technique.

However, the sport theme was not a new creation. Pictures dating as far back as 1716 published in Gregorio Lambrazini's New and Curios School of Theatrical Dancing depict a danced tennis match and Luigi Manzotti glorified a variety of sporting activities in his 1897 epic ballet production for La Scala. For Nijinsky the tennis game provided not an opportunity to celebrate dancers' athleticism, but a pretext to explore both the physicality and psychology of contemporary man.

As the fashionable sport of the times, the tennis theme gave possibility to Nijinksy's idea that a man's body is defined by his era. Combined with the Cubist influence, the fragmented gestures of the dancers were to reveal new possibilities for bodily movement. The 'game' played amongst the trio of dancers illustrated a critique on modern love. The three way flirtation over the search for a lost tennis ball was merely a game, but it was also a sensitive portrait of intimate feelings presented to the audience in an immediate setting. While the exploration of sexuality, passion, jealousy and reconciliation was not new to the Parisian balletomanes, they were not accustomed to experiencing it so directly.

Studio photographs of dancers Nijinsky, Karsavina and Schollar

So why did audiences find it so underwhelming? Probably because the Parisians had come to expect new ideas contained within the settings of the exotic East, classical myths or romantic fairy tales. Perhaps they expected a danced game in which the virtuosity of the Russian ballet would be displayed? But the Ballets Russes were not famed for performing the expected.

As both a dancer and choreographer Nijinsky sought to cover new ground, continually attempting to discover new possibilities of the human body, each time revealing something unexpected to the delight or shock of the audience. After all, Diaghilev always keen to assert the prescience of his productions declared "We will date Jeux 1930!" What distinguished Jeux within the Ballets Russes oeuvre is in its modern setting Nijinsky attempted not to break with ballet tradition, but to evolve it so that the meaning of dance would be clarified and corporal movement would speak directly. It is just unfortunate that the audience of 1913 were unable to understand.