The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

(From left) Sonia Delaunay in her Paris studio, 1923. Liubov Popova in her Moscow studio, 1919

Keen to follow the Constructivist tenet of productive art, Popova answered an initiative for artists to join Moscow’s First State Textile Print Factory in 1923, together with Varvara Stepanova, designing fabric patterns for mass production. Delaunay began producing designs for commercial purposes after the October Revolution deprived her of the income from family properties in Russia. A quilt for her son’s crib had been her first foray into the applied arts in 1911, and in 1918 she opened her first business, the boutique Casa Sonia in Madrid, where she was waiting out the First World War, and on her return to Paris she started Maison Delaunay in 1925.

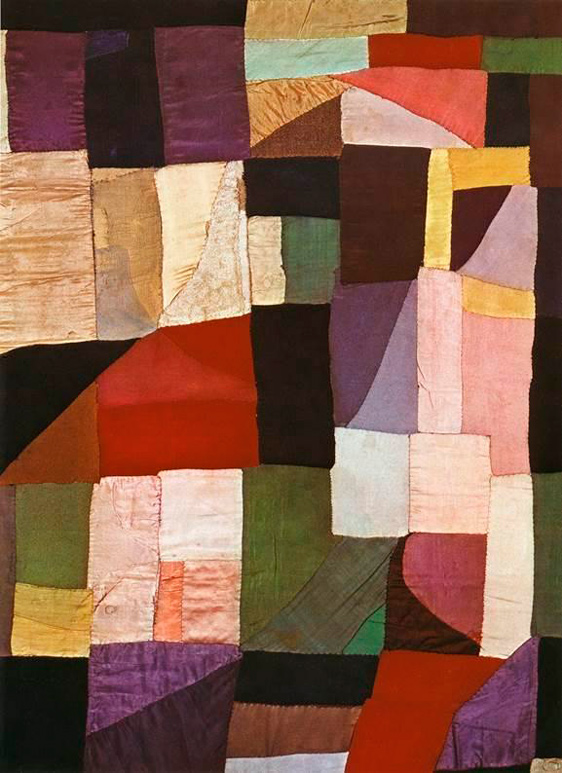

Sonia Delaunay, Quilt, 1911–12

Although committed to the goals of Constructivism, Popova was also aware of the importance of the market, the demands of consumers and the dictates of fashion. In fact, it appears that with Stepanova, she produced fashion shows in which models wore clothes made from their fabric designs. Probably because of these promotional activities, despite tensions between the designers and the factory, Costructivist fabrics had some degree of success and as one contemporary noted: ‘this past spring all Moscow was wearing fabric with designs by Popova without knowing it’. Delaunay’s designs did circulate amongst the rich and famous, including celebrities such as Gloria Swanson and Nancy Cunnard, yet she was also interested in making her designs accessible to the general public. She patented her invention of the tissu-patron, a sort of DIY dress kit that contained fabric printed with a dress-making pattern that matched its decorative design. In a lecture she gave at the Sorbonne in 1927, Delaunay specifically spoke about how this ‘fabric-pattern’ would ‘enable a dress to be precisely reproduced at the other end of the world at minimal cost and with minimum wastage of material’. Interestingly, Delaunay also publicised her invention in the Soviet Union in 1928 in the journal Iskusstvo Odevatsia.

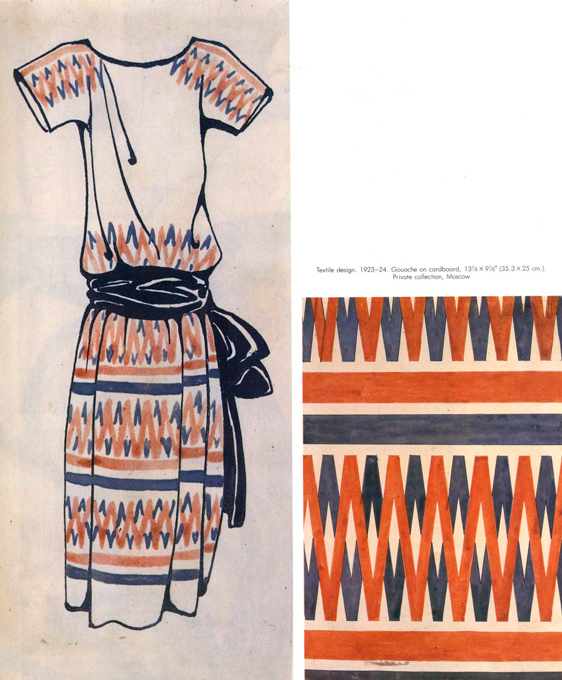

Aligning the printed design with the structure of the dress was equally a concern for Popova. She wanted to become more involved in the production process, in order to control the design of the fabrics in relation to their intended use. Unfortunately, the factory management did not take kindly to this and, like Delaunay’s tissu-patron, this initiative remained within the domain of the theoretical. Popova’s attempts are visible in sketches matching fabric patterns with clothing designs that work efficiently together. However, despite this Productivist veneer, these examples and many other clothing designs by Popova are elegantly reminiscent of Parisian fashion.

Liubov Popova, Textile design, 1923–24

Nonetheless the bold patterns that Popova designed certainly adhered to Constructivist principles and she was criticised by factory management for using a compass and ruler to create her designs. She scrupulously based them on Euclidian geometry and simple shapes, derived from her last experiments with easel painting. Popova also used repetitive forms and primary colours and sometimes introduced a sdvig, a dislocation of the rhythm of the pattern.

Liubov Popova, Textile design, c.1924

Similar elements characterise Delaunay’s fabric patterns. She achieved notoriety due to her distinctive geometric designs in strong colours, adapted from her experiments with Simultaneous colour theory in painting. The notion of dislocation is also present in Delaunay’s designs, for example in the pattern reputed to be the artist’s favourites.

Sonia herself, in her lecture at the Sorbonne, spoke about geometric motifs as a practical choice that allowed her to research the theory of colour interaction though her garments, distancing herself from any suggestion of fashionable frivolity: ‘geometric patterns will never become old-fashioned, simply because they have never been fashionable’. Almost a century later, few could argue that the designs of Delaunay and Popova are not as fresh as the day they were created.