The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

This essay first appeared in the programme for the original performance of The Bolt in 1931. The text has been translated by Mollie Arbuthnot with additional images added by GRAD.

Bolt is the first attempt to create a ballet on the theme of Soviet industry. In 1931 that is, as it were, somewhat late. We recall that the repertoire of drama theatres was quite seriously reformed some years ago, and that even Soviet opera is not just a project but beginning to become a reality (Deshevov’s Ice and Steel, Pashchenko’s Black Ravine, Kniapper’s North Wind etc.)

There have been earlier attempts at a revolutionary upheaval in ballet, but they ended up either in stunted, abstract symbolism (The Red Whirlwind) or in compromised melodrama of dubious taste (The Red Poppy). The epithet ‘red’ didn’t save either case, rather it was mechanically attached to the dilapidated ‘classical’ form of ballet. The ‘revolution on pointe’ led to a most stupid farce and parody. It was necessary to set out on a different path: to refashion ballet from the roots, reforming it as a dance-drama with a sensible plot and a living theme.

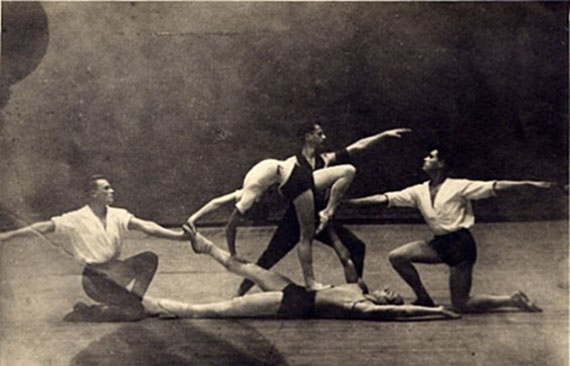

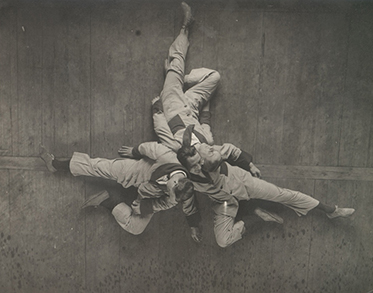

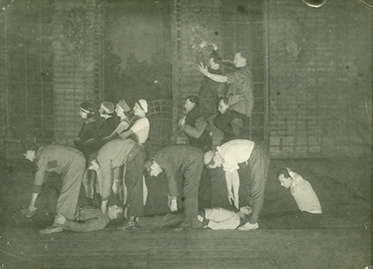

Photograph of rehearsals of The Bolt, 1931, Courtesy of GRAD and St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

So making the leap in ballet to themes of our times turned out to be rather difficult. Centuries of historical tradition are dragging us backwards. Classical ballet emerged in its time as court entertainment, and in Russia, in the Imperial Ballet, it carefully carried its feudal attributes right up to the October Revolution. The stamp of courtly spectacle was clearly marked in ballet even after that. Old classical ballet couldn’t get on with post-October themes. The whole language of dance and the entirety of ballet’s centuries-old foundations needed to be demolished. And that turned out to be much more difficult than the reform of drama and opera.

Dance (like all art) is an ideology. Every movement in dance is not just a spatial movement of the physical body, but also a certain ideological sign. Dance always strives to signify, to express something. The primitive hunter expresses in dance the fleeing beast and the man chasing it. The movements of working the land long ago entered in to ethnic [folk?] dances and circle-dances (ploughing, harvesting, gathering grain etc.). In the arsenal of choreographic art it is possible to detect numerous traces of war exercises and games: we come across them in the life of the Australian savage and in the highly-civilised Greeks in the age of Pericles. In other words, the fundamental element of dance is the movement of production, set to a particular rhythm and lightly adapted to the stylization of dance. In this, the meaningful purpose of productive movement is completely preserved: dance tells a story about something, inspires something.

Photograph of rehearsals of The Bolt, 1931, Courtesy of GRAD and St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

The case of classical ballet is somewhat different. It emerges at the decline of feudal culture, in the spacious halls of the palaces of Italy and France. It is danced by noble ladies and gentlemen, grand princes and marriageable princesses; later, their places are taken by professional dancers, whose mannerisms and gestures imitate the nobles. Classical ballet is not born from imitations of the movements of labour (court circles, of course, did not participate in the production process), but from making elements of court etiquette dancerly: the bow, the ceremonial walk, the reverential curtsey. This too has its own ideology: servility to the monarch, compliance, knightly ‘gallantry’ in relations with women, an atmosphere of infatuation and flirtation. Movements are done at a slow tempo, majestically, without ‘servile’ fussiness: in the sedate world of the court there in no place for nervous haste. The feet are extremely turned out, heels in: that is a sign of a ‘genteel courtier’ in contrast to the knock-knees of ‘low’ people – the peasants and the townsfolk. Class divides are observed even in the gait.

These are the sociological conditions of classical ballet, from Louis XIV to Nikolai II, from the very first choreographic pieces by French court ballet masters to Marius Petipa’s Sleeping Beauty. Over two centuries the idea of ballet became fixed as a purely pleasurable spectacle, lacking any sort of problematic weight. The simplistic plot of a ballet takes place in a fairytale land, and the stage is full of enamoured princes, languid princesses, enchanted swans, evil wizards, airy sylphs floating by, endless hopping variations of ‘genies of the winds’,wood nymphs charming dressed-up swineherds, and crowds of twee peasants merrily joining in with the king’s amusing games. All the blessed inhabitants of this ‘social paradise’ express themselves in the language of an artificial pantomime, send each other cutesy smiles and master various technical feats of dance with frozen expressions on their face.

Photograph of rehearsals of The Bolt, 1931, Courtesy of GRAD and St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

Ballet was preserved in this form right up to the October Revolution. The court style reigned supreme. The individual attempts of talented bourgeois reformers (in particular, one Fokine) drove a wedge into it, but no organic change occurred in classical ballet. The attempt to work on genuinely new dance in a systematic way started only after October.

We will not list all the attempts made by ballet reformers over recent years: their history is unfortunately recounted on countless, amusingly naïve pages. But there was nothing there! At first they tried to juggle with names: the classical duet was renamed the dance of the ‘maiden of the revolution’ and the ‘genius of freedom’, the stereotyped Oriental dance of the veils was supposed to signify the ‘casting off of the veil’ or the burqa, the ‘self-emancipating woman of the East’ etc. The ‘immortality’ of classical stereotypes was declared indestructible: a Komsomol girl was forced into pirouettes, Soviet workers turned tours, Volkhovstroi engineers and Party members prepared to dance with river nymphs. The crown on top of the ludicrous pile of compromises was The Red Poppy, which premiered in the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow, and thereafter toured the whole USSR, including Leningrad. Soviet sailors, the tragic love of a Chinese actress, classical dances between lotus flowers and poppies, ballerinas in tunics from the traditional ‘dream’ sequence, melodramatic ‘baddies’, exoticism – all this led to a styleless dead end, unmasked the compromise of that path, and revealed that creating a soviet ballet was unthinkable while retaining the principles of classical ballet.

Photograph of rehearsals of The Bolt, 1931, Courtesy of GRAD and St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

The movement led by Fedor Lopukhov seems more serious, proposing acrobatic-athletic instead of classical dance Punch 1926, The Ice Maiden 1927, The Nutcracker 1929). The acrobatic training certainly introduced more workable elements than the affected classicism of the nineteenth century. But even here a fundamental mistake is lurking: the revolution in ballet was understood primarily as a revolution in the form of dance. The dance itself remained, as usual, unexpressive and subjectless. There was no thematic, meaningful direction in sight. The human body was transformed into an ideal working mechanism without classical characteristics. If classicism reflected the feudal courtly state, then acrobatic dance corresponded to the mechanised culture of the large, capitalist cities. On the Soviet stage acrobatic dance, with its poorly-thought-through themes, led to formalism.

In Bolt Fedor Lopukhov makes an attempt to move away from abstract acrobatics and create a dance production entirely based on a Soviet theme. For the first time in a ballet libretto we see not exotic China (The Red Poppy) nor a Western café cabaret (The Golden Age) but life on the factory floor. The plot of the ballet shows everyday corruption, drunkenness amongst individual, backwards workers, leading to slovenliness and direct sabotage. The ballet incorporates amateur games and dramatics, political interludes, choreographic billboards, radio-speakers… It’s true that all these elements in the ballet are perfectly familiar to us on dramatic stages: the corrupt clerk is not new, the salopnitsa is familiar, they’ve been successfully marked out in opera (at the flea market in Ice and Steel and also in The Front and the Rearguard – the cliches solidify with extraordinary speed). We’ve all seen the little boy, the loafers and wreckers, the priest with his sexton and devotees… We underline, however, that these figures are seen in ballet for the first time.

Photograph of rehearsals of The Bolt, 1931, Courtesy of GRAD and St Petersburg State Museum of Theatre and Music

We sense one other failure of Bolt: it does not overcome the old principle of divertissement in the ballet spectacle. There is no penetrating movement, no plot, the ending just happens… in the third act, the denoument comes about six or seven minutes after the exposition. Since this is the part with all the action, that is very little. All the rest consists of genre tableaux of a mime-like character, sometimes serious and pathetic, sometimes humorous. In this manner, the divertissement nature of the piece is not liquidated. It is true that yet again in the place of the ‘blue bird’, ‘Prince Khohlik’ and ‘Cinderella’ one by one we see the entrance on to the stage of ОSOAVIAKHIM workers, cyclists, Budenov cavalry soldiers and the like. But nonetheless, the old forms of plot development in ballet make themselves known. The new theme in ballet hasn’t yet found its dramatic expression.

The dances in this ballet, which are far removed from courtly classicism with its arabesques and pirouettes, are built on dance forms of productive movements, taken either from industrial labour (e.g. the textile workers’ dance), or from soldiers’ movements and exercises (the Red Army soldiers’ dance with all manner of tools [weapons?] in the following act). These dance adaptations of industrial movements should not be confused with the machine dances (in the spirit of Forreger’s productions), when the group of participants mimic the movements of the screws and wheels of a machine. The specifics of human labour are lost in such a mechanical interpretation. On the other hand, in Bolt the dance is formed by the productive movements of the worker, rather than a machine. Every profession has its own particular range of movements for a particular purpose, which can also serve as the basic elements of a new workers’ dance. We’re not pre-judging the finished product here, the extent to which Lopukhov has succeeded in conveying industrial movement in dance: we merely point out the general principle.

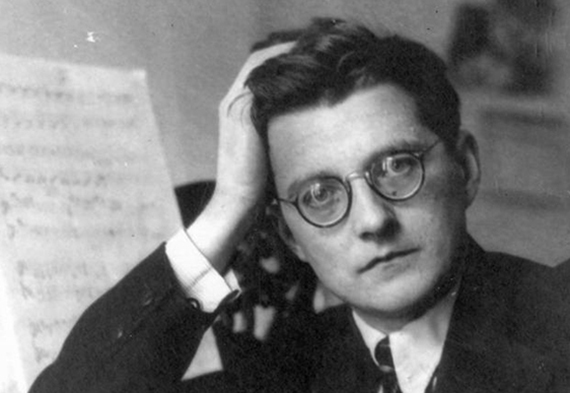

The author of the music for Bolt is one of the most outstanding Soviet composers: Dmitrii Shostakovich.

Irrespective of his youth (born 1906) Shostakovich occupies a particular place in Soviet musical culture. Ideologically close to the ‘left travellers’, Shostakovich gravitates most of all towards large, monumental works. While the majority of Soviet composers currently work predominantly in the sphere of ‘small forms’ (popular songs and ditties), Shostakovich writes symphonies (three: the first, which has now toured all Europe and America; the October Symphony; and the First of May Symphony), operas (The Nose), and grandiose ballet scores (The Golden Age). At the same time, Shostakovich’s music is characterised by a sharp and authentic theatricality: the composer has an ear for dramatic action. In this, his work with Meyerhold is especially significant (on the musical version of Mayakovsky’s The Bug) and particularly with TRAM, the musical section of which Shostakovich has been leading for several years (producing music for Bezymenskii’s The Shot, The Virgin Land etc.). Finally, his universal range and remarkable productivity has enabled Shostakovich to produce a number of works for cinema (New Babylon, and the sound film Alone).

In his ballet scores (the three-act Golden Age and Bolt) Shostakovich follows the line of symphonic ballet, i.e. following in the footsteps of Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky. Of course, with this ‘symphonic’ approach we should not imagine that a purely musical aim takes primacy, to the detriment of theatricality. On the contrary, ‘symphony’ in ballet score is nothing other than the presence of continuous, unbroken movement in the music: the numbers are not fragmentary, but connected by a unity of tempo and the general plan of musical development. Shostakovich’s music is specifically theatrical, realistic (not in the sense of onomatopoeia): every event on stage, every twist of the plot, new aspect of a character or mimetic highlight finds immediate support in the music.

It features bitingly satirical moments (for instance, the ‘Kozelkovshchina’, and the ‘Conference on Disarmament’), but the remainder is dominated by a cheerful and high-spirited mood. As usual, rhythm and timbre (instrumentation) play a prominent role, but the melodic lines are also very pronounced and easily stick in the memory. Shostakovich by no means searches for formal sophistication: the music for Bolt is not loaded with technical complexities, and it is transparent (regardless of the large orchestra) and accessible even to the untutored ear.