The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

In the Russian pavilion money is power and it's in the wrong hands. Russian artist Vadim Zakharov reinterprets the Greek myth of Danaë, who falls pregnant by Zeus in the form of a shower of gold. Conception by pure cash: the ultimate prize for the gold-digging wife, or the banker’s twisted fantasy?

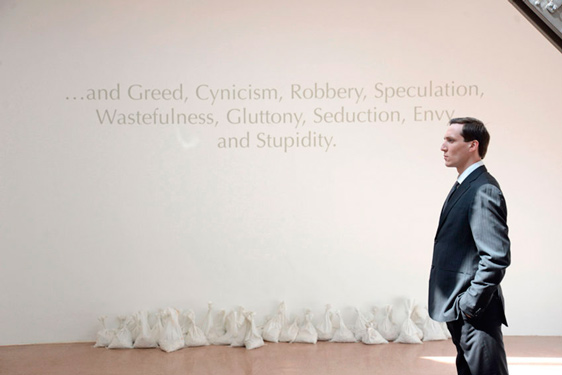

The first of the two rooms presents the very Russian sight of peanut shells littering the floor. Empty husks skitter across the marble, cast down by a saturnine city-slicker on a saddle polished as black as his boots. He sits nonchalantly astride a rafter, impervious to those below. On the wall beneath him the words: "Gentlemen, time has come to confess our Rudeness, Lust, Narcissism, Demagoguery, Falsehood, Banality, and Greed, Cynicism, Robbery, Speculation, Wastefulness, Gluttony, Seduction, Envy and Stupidity."

Installation view from Vadim Zakharov's Danaë. Photo courtesy Daniel Zakharov

For Zakharov, the word 'gentlemen' is not chauvinistic synecdoche for the public at large, but a pointed finger at men alone. His commission takes on the legend of Danaë, whose father shut her up in a bronze tower to prevent her falling pregnant after an oracle prophesised that he would be killed by his daughter's son. Undeterred, the randy Olympian Zeus came to her as a shower of golden rain and knocked her up anyway.

In depicting Danaë, Zakharov signs his name to a list that includes Coreggio, van Dyck, Rembrant, Klimt and, of course, the Venetian painter Titian, for Danaë is no stranger to Venice. Her legend so transfixed Titian that he returned to her again and again. Five of his paintings of her exist today, showing her either naked or clothed, flesh youthful or withered, but always longingly turning to Zeus’s shower of gold. Like Titian, Zakharov considers not only what money does to men, but also its seductive hold over women.

Titian, Danaë with Eros, 1544. 120 cm × 172 cm. National Museum of Capodimonte, Naples

In the second room, male visitors stand around a dark opening into which a stream of glinting medallions pours from the cupola. They strike the floor below like golden bullets, where female visitors are invited to collect them, filling a bucket which is then emptied onto a conveyor by another moody dark-suited oligarch and winched up to the ceiling to complete the cycle.

Of course Putin, oligarchs and money-fixated New Russians all come under fire in Zakharov's theatrical installation, but the real focus here is an older and more universal problem: the power imbalance of the sexes and the critical role of money in this inequality. Zakharov uses the pavilion's visitors as eager pawns who fulfil their roles in the allegory with unsettling obedience. Women shriek and giggle as they dash to gather up the coins, while men, silent and watchful, oversee their efforts with what feels like steely authority.

Installation view from Vadim Zakharov's Danaë. Photo courtesy Daniel Zakharov

Zakharov's installation at the Russian pavilion reveals our uneasiness around money, calling upon both the discomforting wealth of the new oligarchy and also the ancient, enduring fiscal imbalance of the sexes. It's rare to find an installation that succeeds at being both highly enjoyable and strangely troubling. The sharp clinks of metal hitting the ground ring in your ears long after you leave.