The hidden meanings of Destined to be Happy exhibition - The Interview with Irina Korina

10 January 2017 | By

09 January 2017 | By

Inside the Picture: Installation Art in Three Acts - by Jane A. Sharp

19 November 2016 | By

Conversations with Andrei Monastyrski - by Sabine Hänsgen

17 November 2016 | By

Thinking Pictures | Introduction - by Jane A. Sharp

15 November 2016 | By

31 October 2016 | By

Tatlin and his objects - by James McLean

02 August 2016 | By

Housing, interior design and the Soviet woman during the Khrushchev era - by Jemimah Hudson

02 August 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 3: "Are Russians Women?" Vogue on Soviet Vanity - by Waleria Dorogova

18 May 2016 | By

Dressing the Soviet Woman Part 1 - by Waleria Dorogova

13 May 2016 | By

Eisenstein's Circle: Interview With Artist Alisa Oleva

31 March 2016 | By

Mescherin and his Elektronik Orchestra - by James McLean

13 January 2016 | By

SSEES Centenary Film Festival Opening Night - A review by Georgina Saunders

27 October 2015 | By

Nijinsky's Jeux by Olivia Bašić

28 July 2015 | By

Learning the theremin by Ortino

06 July 2015 | By

Impressions of Post- Soviet Warsaw by Harriet Halsey

05 May 2015 | By

Facing the Monument: Facing the Future

11 March 2015 | By Bazarov

'Bolt' and the problem of Soviet ballet, 1931

16 February 2015 | By Ivan Sollertinsky

Some Thoughts on the Ballets Russes Abroad

16 December 2014 | By Isabel Stockholm

Last Orders for the Grand Duchy

11 December 2014 | By Bazarov

Rozanova and Malevich – Racing Towards Abstraction?

15 October 2014 | By Mollie Arbuthnot

Cold War Curios: Chasing Down Classics of Soviet Design

25 September 2014 | By

Walter Spies, Moscow 1895 – Indonesia 1942

13 August 2014 | By Bazarov

'Lenin is a Mushroom' and Other Spoofs from the Late Soviet Era

07 August 2014 | By Eugenia Ellanskaya

From Canvas to Fabric: Liubov Popova and Sonia Delaunay

29 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

My Communist Childhood: Growing up in Soviet Romania

21 July 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

Monumental Misconceptions: The Artist as Liberator of Forgotten Art

12 May 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

28 April 2014 | By Rachel Hajek

An Orgy Becomes a Brawl: Chagall's Illustrations for Gogol's Dead Souls

14 April 2014 | By Josephine Roulet

KINO/FILM | Stone Lithography Demonstration at the London Print Studio

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

24 March 2014 | By Renée-Claude Landry

Book review | A Mysterious Accord: 65 Maximiliana, or the Illegal Practice of Astronomy

19 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

Leading Ladies: Laura Knight and the Ballets Russes

10 March 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Cash flow: The Russian Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale

03 March 2014 | By Rosie Rockel

24 February 2014 | By Ellie Pavey

Guest Blog | Pulsating Crystals

17 February 2014 | By Robert Chandler Chandler

Theatre Review | Portrait as Presence in Fortune’s Fool (1848) by Ivan Turgenev

10 February 2014 | By Bazarov

03 February 2014 | By Paul Rennie

Amazons in Australia – Unravelling Space and Place Down-Under

27 January 2014 | By Bazarov

Exhibition Review | Siberia and the East, fire and ice. A synthesis of the indigenous and the exotic

11 December 2013 | By Nina Lobanov-Rostovsky

Shostakovich: A Russian Composer?

05 December 2013 | By Bazarov

Marianne von Werefkin: Western Art – Russian Soul

05 November 2013 | By Bazarov

Chagall Self-portraits at the Musée Chagall, Nice/St Paul-de-Vence

28 September 2013 | By Bazarov

31 July 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Lissitsky — Kabakov: Utopia and Reality

25 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

Exhibition review | Ilya and Emilia Kabakov: The Happiest Man

18 April 2013 | By Richard Barling

08 April 2014 | By Alex Chiriac

What struck me when confronted by the posters in KINO/FILM: SOVIET POSTERS OF THE SILENT SCREEN was the startling directness of their impact. Competing for attention amongst the flood of political propaganda posters and banners following the Russian Revolution meant that artists sought to ‘employ everything that could stop even a hurrying passerby in his tracks’. The Stenberg Brothers and their colleagues employed dynamic angular compositions using radically distorted perspective, unusual angles and bold, arresting colours.

What I find astonishing is that artists were often given less than 24 hours to design these posters, the results of which combined manual image making skills with mechanical processes. Posters were produced in large numbers using machine-run offset printing processes that had arrived in Soviet Russia in the late 1920s [1]. The urgency with which artists were forced to work contributed to the spontaneity and visual immediacy of the outcome.

London Pint Studio, in collaboration with GRAD, hosted a fantastic lithography demonstration that enabled us to grasp the complicated processes of lithographic printing and appreciate the incredible virtuosity of artists in successfully expressing the character and atmosphere specific to individual films.

[1] The off-set process uses a series of rollers; the image (the right way round) is transferred on to another roller (in reverse) which then transfers the image on to the paper the correct way round. This considerably speeds up the process for commercial production.

THE PRINCIPLES OF LITHOGRAPHY

Lithography is a planographic, or surface, printing process invented in the late nineteenth century. The term comes fr om the Greek lithos (stone) and graphein (to write). It relies on the chemical fact that grease and water repel each other.

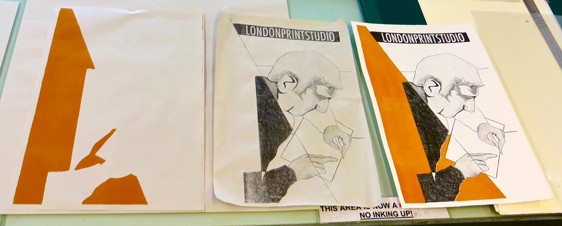

Our Soviet-inspired design in three stages [using two plates]

Our Soviet-inspired design in three stages [using two plates] SIMPLIFICATION AND TRANSFER OF THE DESIGN

The lithographic stone used is an especially fine and porous type of limestone which comes from one particular quarry in Bavaria. In preparation for the transfer of the design the stone is polished with varying grades of carborundum grit until smooth.

Kath demonstrating the design transfer process

Kath demonstrating the design transfer process The design is transferred using red oxide transfer paper, which is chemically neutral.

[2] In Soviet film posters photographic images received from the Film studio would have first been squared up and then projected onto a layout board fixed to the wall. Artists could alter the size of an image by varying the distance of the projector and distort perspective by changing its angle, therefore suggesting the dynamics of film experience. Once complete, the image layout was passed onto the printers to be interpreted by craftsmen who would then transfer the image on to the stone.Testing our mark-making on a carefully prepared stone

The image is then drawn directly on to the stone with a greasy litho crayon. These come in five grades (five being the hardest, containing the least amount of grease) and alter the density of the line created. Tone is achieved through varied mark making. What you see on the stone is how it will look.

Gum Arabic – a curiously sweet and vinegary smell

The lithographic process is all about chemical modification; dilute Nitric acid is added to fix the image on the (alkali) stone, and rubbed with gum arabic to prevent any further grease settling. The stone is then washed, ready for the inking process.

Because the process relies on the mutual repulsion of grease and water, the porous stone must be kept damp prior to inking. Water is sponged on to the surface.

John Milner expertly using two sponges; one wet, one dry (to remove excess)

Greasy printing ink with the consistency of stiff black treacle is applied to the leather roller and then onto the damp surface of the stone. Wh ere water is present, the ink is repelled; wh ere the stone is etched and greasy marks remain, the ink will be attracted.

Lithographic ink is stiff in order for it to stick in the etched parts of the stone (the tooth) – otherwise definition is lost

Lithographic ink is stiff in order for it to stick in the etched parts of the stone (the tooth) – otherwise definition is lost

Busy Inking up the leather knapp roller; Kath from LPS expertly inking the stone; the first of many!

Busy Inking up the leather knapp roller; Kath from LPS expertly inking the stone; the first of many! This inking process is repeated three times, with the stone kept damp throughout.

If the plate is not kept damp enough, the ink sticks to unwanted areas of the stone (right)

If the plate is not kept damp enough, the ink sticks to unwanted areas of the stone (right)

Paper being carefully placed on the stone ready for printing; T bar marks, made on both stone and paper, are lined up to ensure exact registration.

Paper being carefully placed on the stone ready for printing; T bar marks, made on both stone and paper, are lined up to ensure exact registration. The ink is transferred on to the paper by rolling the stone and paper together through the scraper press. The paper has been pre-printed area of flat colour using a photo-lithographic method.

Pushing the bed of the press until the stone is in line with the roller

Pushing the bed of the press until the stone is in line with the roller

Henry Milner pushing down the handle to increase the pressure; the stone is then rolled through, by Rosie Rockel at a steady speed.

Henry Milner pushing down the handle to increase the pressure; the stone is then rolled through, by Rosie Rockel at a steady speed.  The moment of truth: Paper peeled back to reveal the lithographic print!

The moment of truth: Paper peeled back to reveal the lithographic print!

The finished prints!

Thanks to the London Print Studio; a very successful workshop!

[3] See Lutz Becker, KINO: Revolution, Film and Design, KINO/FILM (Exhib Cat.), p.18